RESEARCH CONFIRMS: WE ARE ALL CRIMINALS

Research on self-reported criminal offending shows that almost all teenagers commit some form of delinquency. Indeed, that is true for most teens even if we exclude behaviors that are only illegal for juveniles (possessing alcohol, buying cigarettes, truancy, curfew violations, and so forth). In other words, offending is pretty “normal” behavior for teens, as they push the limits of adult authority, act out their frustrations, look for thrills or something to relieve their boredom and lack of programmed activities, experiment with different identities, and hang out with different friends and acquaintances. The near-universality of teen offending (and even adult offending) is also a product of our society’s choice to make so many things criminal, especially in the areas of traffic law, municipal regulation, and prohibition of soft as well as hard drugs.

We also know that the seriousness, frequency, and persistence of youthful offending is dependent on a number of factors that are not fully within a child’s control. Youthful offending, more than adult offending, tends to be a group phenomenon – basically good people, and especially kids, will do things in a group that they would never do on their own. That is partly because children are more susceptible to peer pressure to go along with what their companions are doing. To some extent, of course, kids choose their friends; they can and do choose not to further associate with other kids who propose and do criminal acts. But these choices are harder if most of the kids in your neighborhood are doing criminal acts. And, as the U.S. Supreme Court has noted in recent juvenile-offense sentencing cases, brain science confirms what we all know from observation and experience: juveniles and even young adults are cognitively and emotionally unable to fully appreciate the consequences of their criminal acts.

Youthful experimentation with crime is typically followed by desistance in the early years of adulthood, although self reports show that even at the age of 30 a substantial minority of persons are still engaging in some form of criminal activity. Most kids and young adults desist from crime as they complete their education, find permanent employment, enter into marriage or a stable relationship, and have children — unless these normal, life-course processes are interrupted and their early criminal career is extended. Again, we should praise those who choose to desist, and may blame those who do not, especially once the offender has moved beyond young adulthood. But some interrupting events are not within the offender’s control. Juvenile and adult criminal justice processing and societal “labeling” of the teen and young adult as a “criminal” can delay the processes of desistance, making it harder for him or her to obtain and keep employment, attract a marriage partner, find suitable housing, and get needed welfare benefits.

And yet — whether any given offender becomes subject to juvenile and adult criminal justice processing, labeling, and debilitating collateral consequences is largely a matter of good or bad luck. Most crimes are not reported to the police, let alone cleared by an arrest, so only a few offenders (and very few white middle class kids) ever get a criminal “record.”

Given this selectivity – which is at best random, and at worst the product of class and race inequalities — it is irrational, unfair, and often counter-productive to give substantial weight to formal criminal records in sentencing and in the imposition of collateral consequences for conviction. The people who are disadvantaged by these policies are not that different from those, like me, who have no formal record.

Richard Frase, University of Minnesota

TACKLING BIAS in the STREETS, COURTROOM, CLASSROOM, and at the CAPITOL

We must tackle bias in the streets and in the courtroom

We must tackle bias in the streets and in the courtroom

Overwhelming statistical evidence reveals racial disparities in Minnesota’s law enforcement and judicial systems. Yes, the land of 1,000 lakes is also the land of the status quo. The American Civil Liberties Union found that in Minneapolis black and Native American citizens are eight to nine times more likely to be arrested for low-level offenses than whites. The consequences of relentless police contact can be fatal: the Star Tribune determined that over the last 15 years, people of color in Minnesota “comprised an average of 16 percent of the population and 30 percent of arrests, but 45 percent of police-involved deaths.”

High-profile incidents such as the fatal shootings by police of Jamar Clark in 2015 and Philando Castile in 2016 have sparked protests and calls for reform. Even as this important work is ongoing, we must also tackle bias in the courtroom.

White juries are more likely to convict black defendants, sometimes disturbingly based primarily on beliefs that the defendant must be guilty. In our ostensibly fair judicial system, black defendants receive harsher sentences than whites for the same crimes. Black and native Minnesotans are badly overrepresented in prison. Part of the problem may be white prosecutors (95 percent of elected prosecutors are white) providing more lenient plea offers to defendants with whom they more easily empathize. This type of bias can be unconscious and requires demographic tracking to detect and active training to counter.

We must tackle bias in the classroom

A truly fair system must account for the implicit bias pervasive in our society, and prevent unscrupulous prosecutors or defense attorneys from using race to advance their cases. Not only must we widen the participation of people of color at all levels (more prosecutors, more defense attorneys, more jurors and more judges), we must support and demand implicit bias training in the classroom. From students of law enforcement (whom I teach) to law and policy students (to name a few), every person should be made aware of their privilege and the extraordinary power they are about to yield in their chosen profession. If students don’t recognize the biases they hold while studying in a safe environment, they will not value people different from them while seeking to provide justice.

And we must tackle bias in the people’s house

Minnesotans serving time in prison or jail and those on probation or parole for a felony-level offense are denied the sacred right to have their voices heard in the democratic process. While this is an issue of principle, it should be duly noted that this is an issue that disproportionately impacts African American Minnesotans as they are seven times more likely to be disenfranchised than White Minnesotans.

Suppressing the right to vote seems criminal. Dr. King in 1957, said “So long as I do not firmly and irrevocably possess the right to vote, I do not possess myself. I cannot make up my mind — it is made up for me. I cannot live as a democratic citizen, observing the laws that I have helped to enact — I can only submit to the edict of others.”

This subject is highly important to me because I was not allowed to vote for the 44th president of the United States due to being on probation. I could not cast a ballot for the first Black president in American history and I must live with that.

Voter disenfranchisement is a serious form of oppression but the subjugation extends beyond casting a ballot. People with records are denied access to welfare benefits, public housing, education loans, and the right to serve on a jury or run for office. These barriers make it extremely difficult to find redemption; the subjugation resembles the Jim Crow laws.

Over the years, I’ve worked with WAAC to help call out the implicit bias that surrounds us, that seeps into our subconscious and fuels the unconscionable statistics listed above. I have taken full responsibility for my actions and have a great deal of regrets for the decisions I’ve made. However, the work of WAAC has provided educational opportunities for me to better understand the reason why I was severely impacted while others were never held accountable. WAAC is shifting paradigms by acknowledging that we’ve all fallen short of our best but, most importantly, we all deserve a chance to transcend our poor decisions.

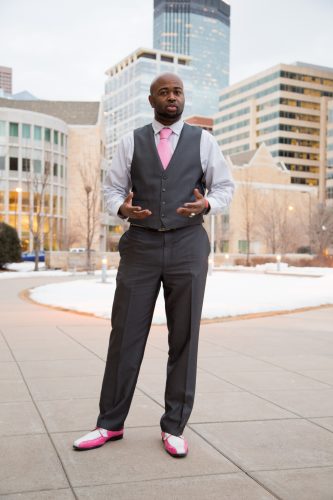

Jason Marque Sole, ABD, is the Minneapolis NAACP president, an adjunct professor in Hamline’s Criminal Justice and Forensic Science Department, and tenacious leader of social reform. His book, From Prison to PhD is a memoir of hope, resilience, and a second chance. Jason hosted the first WAAC talk; the audience were his students: future and current law enforcement officers.

HOPE FOR A MORE JUST SOCIETY

As a person of color and recent law school graduate, I know all too well the importance of racial equity. Unfortunately, I have seen how much work still needs to be done so that we may achieve it in our communities.

Growing up, I witnessed what I believed to be unequal and unjustified treatment by police officers towards my friends of color and me compared to white peers. We were often pulled over and deemed suspicious as officers conducted fishing expeditions, searching for contraband we did not possess, or evidence of crimes we had not committed.

I have two sons. Two brown sons, whom I love. I am raising them to be upstanding citizens, yet I have a real fear that they will experience some of disparate treatment that black and brown boys and men of color face all too often.

While in law school, I gained the knowledge and practical experience that will allow me to change the lives of people around me. Earlier this month, as I crossed the stage to collect my diploma to the sounds of my family and friends cheering me on, I thought: What a time to be a lawyer! From the Capitol, to the courtroom, to the classroom, to the streets, we are converging at a crucial moment in time that is testing and calling upon us all. We are defining history.

Last week, I had the opportunity to join the Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) Organizing for Power: Inside and Outside Strategies speaker series. As a presenter and panelist, I spoke of WAAC’s effort to increase community awareness about the life-altering consequences people of color experience when they commit (or are accused of committing) crime, and how much more egregious those punishments are than those often experienced by white people who commit similar crimes. Aligned with our mission, I also made a case for why those who have been incarcerated should not be further marginalized and isolated—but rather provided opportunities for a second chance to foster a more just and equitable world. I provided elected officials, staff and senior administrators with a closer look at how everyday people are coming together to acknowledge that the justice system needs to be more racially equitable.

I spoke of these legal inequities, not just from a law graduate’s perspective, but also from the heart of a someone who watched her mother be beaten by the police, whose friends and family have missed out on life because they were behind bars for doing the same thing others do with impunity, who is so excited and so terrified to watch her own sons grow up to be young men of color in America.

So what can you do about it? As I mentioned to the GARE community and in the words of author and attorney Bryan Stevenson, I would suggest that you get close. Meet your neighbors, break bread together, share and listen to each others’ stories. You will see and learn that you are no different or better than them.

But first, take a moment to look in the mirror. Recognize your own flaws, your own biases, your own shortcomings. Ask yourself, What have I had the luxury to forget?

WAAC changes the way we see others by challenging the way we view ourselves. We all have done things in our past, but many of us have been fortunate to have experienced empathy and mercy that we can now share with others. Let us not neglect to acknowledge and seize opportunities to extend mercy, to change the lives of others, and in doing so, change our own.

I’m asking you as a soon-to-be lawyer, as a daughter, as a mother, as a neighbor, as a friend: join me in the call for racial equity and mercy within our legal system. You needn’t be a lawyer to seize any one of the countless opportunities that lie ahead of you to do your part to reshape what that looks like.

We are all here for a time such as this. A time to fight, a time to shield, a time to ensure true justice for all. Now, let’s work together and do our part to make a difference and make our mark on the world.

Nadine Graves, J.D., is a recent graduate of Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota, where she focused on public interest areas of law. Nadine has served as the student director of the Child Protection Clinic, editor of the Journal of Public Policy and Practice, and as a mentor through the Open Doors to Federal Courts program. She is also a WAAC Board Member.

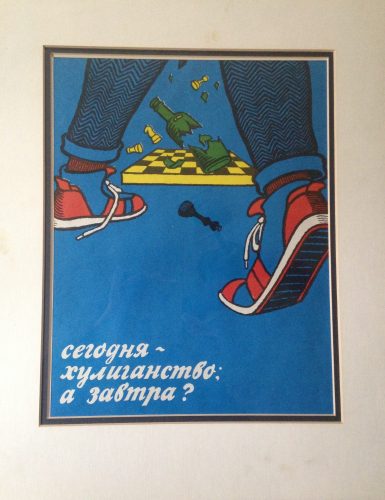

He’s a hooligan today; what will he be tomorrow?

As a punk rock kid, trouble-making was the go-to prescription for boredom and my crew of cretins, kooks, and anarchists were always looking for new partners in mayhem. At one point, the communal house/meeting space/print shop/music venue where I was living became a crash pad for groups of train-hopping punk kids when they’d come through town. It was pretty typical to get up in the morning and discover 5-10 new temporary roommates snoring away on the living room floor. And anytime a new crew checked in it was an excuse for us locals to raise a little celebratory hell. One frequent guest,

As a punk rock kid, trouble-making was the go-to prescription for boredom and my crew of cretins, kooks, and anarchists were always looking for new partners in mayhem. At one point, the communal house/meeting space/print shop/music venue where I was living became a crash pad for groups of train-hopping punk kids when they’d come through town. It was pretty typical to get up in the morning and discover 5-10 new temporary roommates snoring away on the living room floor. And anytime a new crew checked in it was an excuse for us locals to raise a little celebratory hell. One frequent guest,

And anytime a new crew checked in it was an excuse for us locals to raise a little celebratory hell.

One frequent guest, partner-in-crime, and occasional long-term couch resident was a young woman who’d been traveling around surreptitiously by rail for a couple years. Her family were Russian emigres and had a business selling Soviet-era memorabilia online; she often had interesting items from their collection stowed in her backpack to give to friends along the way. After several exciting and terrifying misadventures of possible/certain illegality together, she gave me the poster in the photo. According to her, the Cyrillic translates to “He’s a hooligan today; what will he be tomorrow?” I, naturally, loved it immediately and it’s made its way onto the wall everywhere I’ve lived ever since.

These days, the poster hangs right beside my front door. Every time I leave the house, it makes me think of those days, how I pictured my future then as a youthful screaming bomb-thrower, and how strangely different that future has turned out. There is certainly some luxury in forgetting the indiscretions of youth, but the real value more often comes from remembering and carrying those experiences with you.

Anyway: now this image is also a reminder that this grown-up hooligan owes it to his younger self to make the path from an uncertain to a constructive future a little easier for others, if I can. I truly appreciate having the opportunity to do that (in my very small way!) supporting WAAC.

B.G., WAAC advisor